search the Original Green Blog

Note from Steve: I’ve had a long-running neighborhood structure discussion with Chip Kaufman that stretches back for years, but it has been far too spotty to date due to time limitations. I posted a few months ago asking Where’s the Edge of the Neighborhood? Chip offered this essay in response. I have high hopes that we might actually resolve this question in what I hope becomes a running series of posts here on this issue. Also please note: the diagrams are Chip’s, whereas the photograph (from a commercial centre of Islington in London) is mine… and I have lightly edited his essay for its current setting in a blog versus its original setting in a book.

A difference of understanding among New Urbanist practitioners about town and neighbourhood structuring risks dysfunctional urban structures on the ground for some New Urbanist projects, and this problem urgently needs to be resolved. New Urbanism is structured around the walkable neighbourhood. It is imperative that we address the challenges of achieving viable neighbourhood centres. A resolution is needed.

In my view, the urban structuring problem is currently manifesting itself in certain designs for ‘neighbourhoods’ without feasible centres, and oversized and/or badly structured towns. Such structuring needlessly limits walkability, public transport, local jobs and social interaction. The following will explain urban structuring at the scales of towns and neighbourhoods.

Urban centres have always capitalised on custom by locating at intersecting trade routes. This applies to all urban centres, including smaller neighbourhood centres. However, mid to late twentieth-century sprawl road network planning concentrated vehicular traffic into oversized and too widely-spaced trunk roads instead of providing for more dispersed, smaller-scale and direct street networks.

This relatively coarse movement network planning has spawned oversized shopping centres at oversized intersections, capitalising on oversized and more car-dependent shopping catchments. Neighbourhood centres within these oversized catchments, deprived of custom by an overly coarse movement network that bypasses them, will wither and never be able to deliver the vibrant social and commercial interaction that the local community and economy deserves. In our experience, such urban structuring problems come from an insufficient understanding of the ‘Movement Economy’.

‘Movement Economy’ is a term coined to describe the relationship between an urban centre and the combination of its location within its catchment, and how well the street network ‘feeds’ that centre. A beneficial Movement Economy will optimise the position of its centre between being central to its walkable catchment, and locating the centre to maximise ‘capture’ of custom flowing through it daily, en route to and from a larger destination such as a city centre. Structure planning that isolates community or neighbourhood centres away from the Movement Economy will deny such centres of crucial commerce (as well as public transport), which should

also bring people to such centres.

Any informed observer of sprawl and/or post-war English new towns will recognise this systemic planning error, where neighbourhood centres were systematically isolated from the Movement Economy. Those centres continue to struggle because their community facilities alone cannot attract enough custom or activity. Community and Commerce are compatible and interdependent, as they always have been. Urban structuring can and should combine the two, to their mutual benefit.

We should not be perpetrating English new town or sprawl problems in Australian New Urbanism. As with English new towns, the town and neighbourhood structuring in certain plans separates the neighbourhood centres from the Movement Economy. On the other hand, urban structuring, whose Movement Economy feeds all centres including neighbourhood centres, will optimise their sustainability.

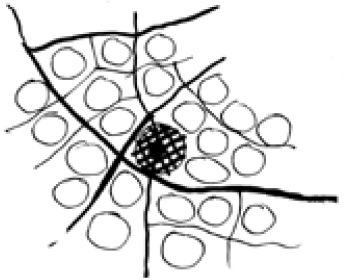

The following diagrams clarify the assertions of this essay. The circles indicate walkable neighbourhood catchments, with radii from their centres of about 400m, which is generally about a five-minute walk. The finer-grained street networks are not shown, but neighbourhood connectors and the arterial network are. Diagrams 1A and 1B show how a neighbourhood centre can be fed by or deprived of the Movement Economy.

diagram 1A

Diagram 1A shows a neighbourhood centre fed by the Movement Economy and bus transport via ‘Neighbourhood Connectors’, which can usually be just two-lane streets when the regional movement network has a filigree of such connectors spaced at about 800m and passing through each neighbourhood centre. In this context, and with at least 800 dwellings, most neighbourhood centres should support the synergistic co-location of a corner store/café/deli, childcare centre, bus stop, and possibly other small businesses and home-based businesses.

diagram 1B

Diagram 1B shows a neighbourhood centre deprived of the Movement Economy and with little hope of a bus passing through its centre, because bus routes generally follow the larger movement network that links major destinations most directly. All that these deprived “neighbourhood centres” can hope for is a small park and maybe a community centre of some sort, which is likely to struggle for users because most users are out on the main movement network heading to other important destinations. This is not, in our view, really a neighbourhood centre, within the principles and objectives of the New Urbanism.

diagram 2A

Diagrams 2A and 2B show neighbourhoods clustering to form towns, the first with a more viable structure, size and Movement Economy than the second. Diagram 2A shows a town centre that is its own walkable catchment with a 400m-long main street, which has eight neighbourhoods clustering around it to form a town. At 15 dwellings per gross hectare, this catchment can support about 18,000 people, which is generally enough population to support two competing supermarkets and a wide range of businesses and community facilities at its town centre. Of course, when applied to real sites, such a diagram needs to adjust to fit its context.

diagram 2B

Diagram 2B shows a town and neighbourhood diagram promoted for two decades by Duany & Plater-Zyberk in Miami and its followers. Its four neighbourhoods are separated from the main Movement Economy, which passes between them to serve the town centre. But this town centre, with its stronger attractions, creates its own de facto walkable catchment, and thus starves the neighbourhood centres located about 500m from the town centre, of custom and purpose. At 15 dwellings per gross hectare, this may support a population of only 8,000 people, which may barely support a small supermarket centre, plus relatively limited businesses and community facilities because of its smaller catchment.

Such a small town centre has little chance of competing against the larger usually stand-alone single-use regional shopping centres, which have proliferated across much of Australia and the Western World. Diagram 2A has a much better chance of competing against stand-alone regional shopping centres, because with its larger population it can offer a wider shopping choice, co-located with other business and community destinations.

The plan for the Western Sydney Urban Land Release, the Public Transport Plan for the Leneva Valley (Wodonga), and the plan for West Dapto all show how these towns will occupy and serve their own catchments, complementary with and efficiently feeding public transport into the single regional centre or city centre. Located to optimise the regional Movement Economy, the regional centre or city centre is the same structure as Diagram 2A, but it has more population density and a higher concentration of higher level services, jobs, government and culture.

Diagram 2B has further structural shortcomings in my view. It is impossible for a bus route efficiently to serve both the neighbourhood centres and the town centre, without a very circuitous route. The urban structuring of Diagram 2B needlessly cripples both its neighbourhoods and its smaller town centre, in comparison to Diagram 2A.

On the other hand, the neighbourhood centres in Diagram 2A are at least 800m from its town centre, and they are fed by the Movement Economy and public transport, meaning they will be more viable economically, and thereby also better for community interaction.

diagram 3

Diagram 3 shows an overly large grouping of over 20 neighbourhoods, with one very large town centre with a population at 15 dwellings per hectare of 40,000 or more. Large supermarkets, discount department stores, bulky goods and other car-based retail will jump at the chance to locate in that town centre, exactly because it is has a very large and cardependent catchment. Of course, the downside of this model is that all the neighbourhoods outside the inner ring around the

town centre are doomed to travel a needlessly greater distance to reach daily needs and jobs. Plus most public transport will be travelling along the main movement network, which bypasses and deprives all these neighbourhood centres of custom and resultant viability.

It is important to tune the movement network to disperse traffic (custom) to feed neighbourhood centres, town centres, regional centres and city centres. To help ensure economic viability for neighbourhood centres, each neighbourhood connector should carry from 3-5,000vpd and the movement network should at least accommodate public bus transport from commencement of development. This volume of vehicular traffic can quite feasibly deliver high pedestrian/cyclist amenity and safety.

To deny this traffic volume from the neighbourhood centres is to deny their economic viability, and in turn will needlessly force too much traffic onto larger arterials, increasing vehicle kilometres travelled, car dependence and retail gigantism. Well-tuned slow-speed traffic dispersion through the neighbourhood centres will also reduce the prevalence of giant intersections in coarse movement networks, and the resultant need for such measures as dual couplets to accommodate the needlessly high traffic volumes.

left: street network shows how Movement Economy feeds all centres

middle: distribution of neighbourhoods, whose catchments do not overlap

right: towns formed by neighbourhoods clustering around town centre walkable catchments

The three diagrams above, provided courtesy of Peter Richards of Deicke Richards in Brisbane, document the existing urban structure of Inner Brisbane, which demonstrates the urban structuring advocated here. This part of Inner Brisbane has withstood the test of time and will continue to flourish because its urban structure feeds all centres with good Movement Economy.

Hopefully this will clarify what the ‘neighbourhood’ circles on plans in this book should mean, and the need for continued debate on this issue, which is so pivotal to urban sustainability. Australian New Urbanism needs to and can structure the complete hierarchy of vibrant and complementary urban centres, including neighbourhood, town, regional and city centres.

~Chip Kaufman