search the Original Green Blog

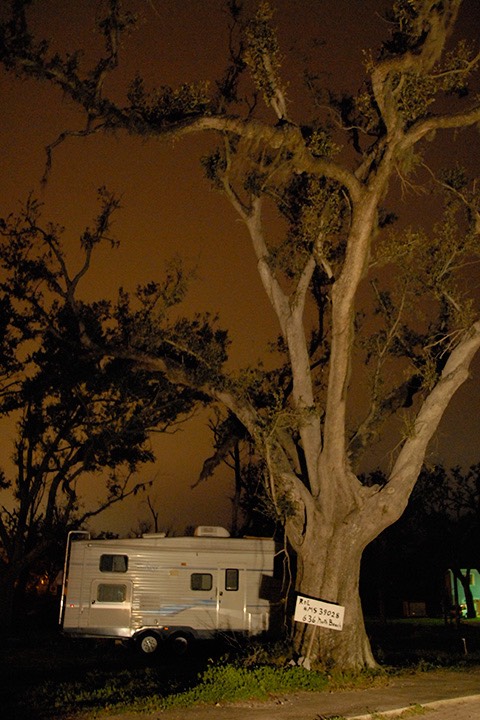

All images on this post not depicting Katrina Cottages are from my upcoming book Nightfall on the Coast, which is a look back at the impacts of Katrina’s devastation ten years later.

Katrina Cottages were once the shining star of the New Urbanists’ work on the Gulf Coast after the storm, but they seem little more than a distant memory today. Much has been written about their failure, but that’s not the whole story. They live on today in unexpected ways.

The Katrina Cottage roller coaster began ten years ago right now, with the monster storm making landfall near the Mississippi/Louisiana border. I was on the road for several days before and after landfall, and came home thoroughly exhausted and emotionally drained from watching those events unfold that week in one of my favorite parts of the world. Wanda greeted me at the office door the evening of September 1 and said “you must call Michael Barranco right now. It’s urgent.”

Michael said “Steve, we’re assembling a Governor’s Commission to figure out how to rebuild the Mississippi coast, and we’d like you to come and speak to us about rebuilding according to the principles of the New Urbanism.” I said “That’s far too big a job for me; let me call Andrés Duany.” The next morning, I went to DPZ and met Andrés, and he said “that’s too big for me as well; we need to call in the entire Congress for the New Urbanism.” And so he picked up the phone and called CNU CEO John Norquist, setting in motion what became the largest planning event in human history, otherwise known as the Mississippi Renewal Forum.

I returned to DPZ the next day, and Andrés and I spent that Saturday afternoon laying out the next steps. He said that some of the emergency housing installed in Homestead after Hurricane Andrew had been removed just one year before Katrina. “Some children started first grade and graduated from high school living in the same FEMA trailer. We really must do better than that.” So our first conception of the Katrina Cottages was “FEMA trailers with dignity.”

It didn’t take long for that mission to grow. Early numbers suggested that a quarter-million homes had been lost in New Orleans alone. The New Orleans construction industry had been building roughly 1,000 homes per year before the storm, and at that rate, it would take 250 years to rebuild. Clearly, we had to be able to deliver housing through every means available: conventional construction, panelized houses, modular houses, and manufactured houses.

It also became clear that the FEMA trailers were more expensive than they seemed. Although FEMA wasn’t forthcoming with the numbers, the evidence we could gather suggested that the entire cost of manufacturing, commissioning, decommissioning, and disposal could be $50,000 to $70,000. If the Katrina Cottages fulfilled the first mission of having dignity, why couldn’t they be permanent as well? Weren’t we being good stewards of the government’s money if we could use that money to build cottages that would last for a hundred years, not just 18 months like a FEMA trailer?

I designed the first Katrina Cottage, then used it to illustrate the principles of the cottages in a call for designs to the members of the New Urban Guild. Designs began to pour in almost immediately. Thus began several years of pro bono work by Guild member on the cottages and other aspects of Katrina recovery. Six weeks after the storm, Guild members made up most of the architecture team, and filled slots on several planning teams as well, as nearly two hundred architects and planners gathered in a Biloxi casino to craft rebuilding plans at the Mississippi Renewal Forum.

My sister Susan Henderson led the architecture team; my role at the Forum was to manage FEMA, but it was almost hand-to-hand combat because they weren’t budging from their policy of only installing temporary housing. They said “if you want us to do something permanent, you’ll have to get an Act of Congress!” My response was “if that’s what it takes, that’s what we’ll do!” And so we did. Congress approved almost a half-billion dollars for the cottages, initially with instructions that they could remain permanently. But in the end, FEMA did what they always do, and pulled them out and auctioned them off.

During the Forum, architecture team member Marianne Cusato was one of several people designing cottages, and Ben Brown gave one of her designs to a newspaper reporter. In the ensuing stories, Marianne’s design got a lot of good responses. In early December, we had a stroke of excellent luck: one of the outdoor exhibition slots at the upcoming International Builders Show in Orlando opened up, and the promoters wondered if we might get a Katrina Cottage built in time. I debated whether to have Marianne or Eric Moser design the cottage. Eric had been published many times in Southern Living over the years, and was considered a star by millions of readers, but Marianne’s cottage had gotten a lot of good press since the Forum, so I asked her to do the design. The little yellow cottage stole the show at the IBS. Later, it won the People’s Choice Award at the Cooper-Hewitt National Design Awards. I credit the cottages and in particular Marianne’s design with helping to turbo-charge the Tiny House movement, which had been largely unnoticed beforehand.

I published Emergency House Plans in early 2006; the designs were done by over a dozen Guild architects. But there was a problem with every cottage in the book. Because space was so precious in tiny cottages, the exterior walls quickly got gobbled up with baths, closets, and kitchen cabinets. In other words, things that are hard to move. So none of the first generation of cottages expanded very easily. And that’s a problem because someone is far more likely to buy or build a tiny cottage if it were obvious how it might grow than if it’s not, so the inability to grow easily was stifling the cottages. And that held back our idea that the cottages could be the first toe-hold back onto your lot, from which you could expand into a larger house later on.

I had the original idea for the next generation of cottages that could expand easily at the Forum, but was so busy doing battle with FEMA that I didn’t have time to develop it beyond just a quick sketch. I called the idea the Kernel Cottage, because it could sprout and grow from several places, like a kernel of grain. Its development had to wait until the summer of 2006, when Ben Brown asked me to design three Katrina Cottages for USA Weekend, which was USA Today’s weekend edition at the time. I did a vernacular, a mid-range, and a classical design, and USA Weekend published them and conducted a poll. The classical version won in a landslide. USA Today was trying to help jump-start the manufacturing of the cottages, so they asked us to find a manufacturer who would produce the winning design in a factory and bring it to Washington DC, making it the first cottage to venture outside the Gulf Coast. It was slated to be donated to a needy resident of Silver Spring, Maryland.

The effort to get the cottage built correctly was herculean; I even spent nights in the factory because nothing we were doing was “normal,” and the workers were working around the clock. Finally, the cottage shipped, and was put on display for several months in Silver Spring. It was during this time that I met Bobby Kennedy, Jr. and his family, who had a keen interest in helping promote the cottages. He later wrote the Foreword to the Original Green book. Unfortunately, this part of the story has a dark ending: after several months on display and after having gotten lots of great press, the manufacturer had an egregious ethical lapse and reneged on their promise to donate the cottage, and towed it away instead. I still wonder where that little cottage ended up.

phantom piers of destroyed house

stand vigil in the gathering

Gulf Coast darkness

The Act of Congress wasn’t working out so well, either, and much of it was our fault. To be blunt, we mis-managed the cottage initiative because we weren’t all on the same page, and the people managing Mississippi’s allocation of several hundred million dollars finally got tired of our infighting and decided to go their own way. The Mississippi Cottages bore many similarities to our designs, but we could have helped improve them had we handled it better. And the cottages always had one fundamental problem: so long as they resembled mobile homes, they were susceptible to the strong rejection of mobile homes that most communities exhibit. Like I told the mobile home manufacturers every time I spoke at their conventions, “it’s not good enough to produce homes as good as site-built homes. Your homes have to be substantially better. So much better, in fact, that instead of signing an ordinance banning your homes from town, the mayor is signing a check to buy one of your cottages.”

To date, we simply haven’t gotten there with any home produced on an assembly line. For a year or so after those heady days surrounding the Forum, I had high hopes that we would change the American home manufacturing industry, but it was never that simple. In the words of one CEO in the early autumn of 2008: “Steve, I can’t just start manufacturing these cottages in my existing factories. They are so different from what we build now that they not only require a different set of construction materials, but they also will require a different set of employees. We have a current culture of building mobile homes, not manufacturing architecture. And so we’ll need entirely new factories, with an entirely new workforce that has a different culture of building. That’s an investment of millions of dollars.” And in retrospect, he was right, as we were descending into the winter of the Meltdown, and the ensuing Great Recession.

By the time 2009 dawned, it seemed that all was lost. Not only were the Katrina Cottages looking all but impossible to produce, but the planning efforts on the Coast were meeting resistance as well. It seemed as if inertia might finally win out. I learned that year that even the name of the cottages was a mistake. Southerners are often much too polite for their own good, so it’s no mystery that it took four years for a New Orleans citizen to finally tell me “Steve, you made a huge mistake. ‘Katrina Cottages’ are ‘Losing Everything I Ever Owned Cottages,’ or ‘The End of My Life as I Knew It Cottages.’ How could you guys possibly name them that?”

But that’s when the cottages began to spawn new life. The New Urban Guild held a summit at DPZ’s office in Miami in January 2009 intent on launching Project:SmartDwelling, which sought to reinvent the American home at half the size and 60% of the cost of a typical American home by building radically smaller and smarter. In the years since, nearly every one of the SmartDwelling techniques turned out to be lessons we learned by figuring out the Katrina Cottages.

Shortly afterward, Lizz Plater-Zyberk did a characteristically generous thing for which she and Andrés are legendary: she called me and said that the Wall Street Journal was doing a Green House of the Future story for which they had asked DPZ to design a house. Because she knew I was writing the Original Green book, she said she would prefer for me to design the house. The article was published April 27, exposing SmartDwellings to a broad audience for the first time.

But it hasn’t yet gotten built. And for the next few years, SmartDwellings went dark, existing only as a great idea that had not yet been realized, as Guild members struggled through the Great Recession like most other architects. That began to change May 12, 2012. On the last night of the Congress for the New Urbanism in Palm Beach, I told my friends Eric Moser and Julie Sanford “if we don’t do anything radical, the SmartDwellings may forever remain nothing but talk and drawings. If we’re committed to seeing them implemented, we need to create a design firm dedicated to the implementation of these ideals. We founded Studio Sky shortly thereafter, and today, there are hundreds of SmartDwelling rising on distant shores. I hope some of ours get built in the US sometime soon. Not only that, but there’s now a high-quality manufacturer gearing up to roll SmartDwellings off the assembly line. I’ll have much more to say about that just as soon as the production goes live. After all these years of thinking all that effort was lost, it seems like it’s finally happening.

I know other Guild members have been working on SmartDwellings as well, but don’t yet know the details, other than Bruce Tolar’s heroic Cottage Square in Ocean Springs, Mississippi. For so long, nobody has had budgets for travel, and now that we’re busy again, nobody has time for travel. But we really do need to get together and compare notes at another summit. Anyone interested in listening in when we do?

~Steve Mouzon

Legacy Comments

Ann Daigle · Works at CityBuilding Exchange

Steve, my take is that the Katrina Cottage was a successful national symbol for dignified, Lean public housing - and that is a very, very good thing. The execution of the idea, in a state where inequity prevails and in a nation not quite ready for inexpensive and Lean (pre-recession!), was less successful. No matter how many worked hard to manage the culture, the mobile home industry cannot be changed. Marianne's idea and push for the Lowe's Kat Cottage distribution model was the most brilliant idea of all, and would have been much more successful had the market been ready and if others had been on board to make it the default. I also think that if SmartDwellings had been built in Mississippi and especially in New Orleans (rather than Make It Right) the lesson abotu sustainable architecture would have gained huge national success. Bottom line, everything you write about, and all the people involved, were really before their time...but the lessons remain!

Steve Mouzon · Board Member at Sky Institute for the Future

Ann, the Katrina Cottage name played very well on the national stage, just not locally to those whose lives were turned upside down. At least that's what they told me. As for the mobile home industry, you've known me long enough to know that I never say never! As a matter of fact, I'm really excited about the company that's gearing up right now to produce them. That's not what they manufactured before... their previous products were very high-precision, high-quality. But that's all it takes is getting it right in one place; Seaside taught us that, didn't it?

Aug 31, 2015 6:23am

1,066+