Living Traditions

The greatest mystery of sustainable architecture in our time has been this: how was it possible for people around the world to pass down to the next generation the secrets of building sustainably according to regional climate, conditions, and culture, especially for the majority of human history when most people could not read or write? Without being able to understand this mystery, the likelihood of starting new living traditions remained close to zero.

The quest to recover the key that unlocked the secret of living traditions spread over two dozen years, from the day after Thanksgiving, 1980 until July 21, 2004. The pattern book that encapsulated what had been recovered was completed on the day after Thanksgiving, 2005, precisely a quarter-century after the search began. The story is told in its greatest detail here on the 40th anniversary weekend of the beginning of the search. I encourage you to read the full account, but it comes down to this: if every pattern of architecture is framed with four simple words, everyone is allowed to think again instead of just obeying the experts. Those four words are "we do this because..." A living tradition is therefore the original crowdsourcing.

Living Traditions are the Operating System of the Original Green Platform. A Living Tradition evolves from generation to generation to meet the needs of the day. Dead tradition is a book of rules. Anti-tradition is a book of prohibitions. A Living Tradition is a dance between young and old, known and mysterious. It also creates the most modern of architecture. There is no architecture more modern than that which is a product of a living tradition because many minds continually update it, but it is truly traditional, not just traditional-style, as well. Bring living traditions back to life and the religious wars of architecture can end.

Living Tradition Principles

What in the world, you might ask, does this landscape have to do with a living tradition? On one side of these hills, life is thriving; on the other side, it's nearly dead. Just a slight tipping of the land makes all the difference. A living tradition that can be sustained for a long time is one which begins by tipping the balance in favor of that which can take on a life of its own and spread. It is far more efficient to set things in motion which are predisposed to continue on their own than to try to manufacture everything with high energy and brute force. But to do so, it is first necessary to have the humility to learn the things the humans love, not just the architects. That which can reproduce and live sustainably is green; that which is incapable of doing so is not green. This is the standard of life. Life is that process which creates all things green.

Patterns

Patterns are things we do repeatedly. Some are good; some are bad. Bad habits are things we do because of weakness. Living traditions are made up of patterns we do because of love. But because we're human, not everything we love is good. See Cautions later on this page for warnings about things done for love that could end badly.

Patterns of architecture or patterns of urbanism can each make up pattern languages that can guide the places and the buildings we build. In pattern languages, each pattern is analogous to words in a spoken language and there are rules of syntax for how patterns are used together.

Great Variety in a Narrow Range

No two snowflakes are alike, nor are any two oak leaves or any two people, even those born as identical twins after a few years of life. Christopher Alexander called this the "quality without a name," or QWAN for short among his colleagues,which is the signature quality of a product of nature or natural processes. My name for this quality is clunky and I'd love to hear a better alternative someday, but the principle holds true: they are identifiable by their species, but differentiated in their individuality.

No human will ever be mistaken for a rhinoceris, a frog, or an eagle, but you also know the difference between your friend and a stranger at fifty feet in twilight. Mechanically produced widgets, on the other hand, are discernible only by make, model, features, and color scheme. Millions could be totally identical except for their serial numbers. But architecture can be more like nature than that, and usually is in great places. These two New Orleans galleries follow the same pattern, but everything varies in some way from one to the other.

Talent Efficiency

Boston City Hall is widely regarded as "a building only an architect could love." A discipline like architecture that requires brilliance every day produces this sort of failure from time to time, even at the hand of the most brilliant masters, and every day at the hand of everyone else. The excuse given by architects for why this building is so widely hated by Bostonians is that "the architect who won the competition for the design of this building wasn't good enough." But even the greatest of masters from Le Corbusier to Frank Gehry had their off days.

This problem with architecture began with the proposition that started gaining traction about a century ago that "if you want to be a significant architect, your work must be unique." Blame lies partly on the architectural press and the architectural academies, but its foundation was the culture of the age which was built on novelty. This seemed warranted by advances into never-seen-before territory beginning with fossil-fueled industry, and then into every realm of everyday life, from the comfort of the Thermostat Age to labor-saving farm equipment, transit which opened up the suburbs, the internal combustion engine which made the automobile possible, and rural electrification.

My parents were born into a rural world lit by kerosene lanterns, fed from a wood stove, and with travel by horse and buggy, and personal necessities handled in outhouses. But by their early adulthood, the modern world had arrived. Great things seemed possible everywhere by discarding the old in favor of the new. How could novelty not be a virtue?

Some of the most important babies thrown out with the bathwater in that age were living traditions in many realms of life, from agriculture to architecture. Living traditions had many benefits, including the fact that wisdom long-proven to work in a particular region allowed everyday practitioners to work with far greater efficiency than those who must stop and think about every move they make if everything they do must be some new invention. Put another way, people with everyday talent working within living traditions could do good work as effectively as geniuses working under the burden of the necessity of uniqueness.

It took about a half-century to even begin to see the error of trashing living traditions, and even now, there is much disagreement on whether this was even an error. In Evil Geniuses, Kurt Andersen pegs 1970 as "Peak New," and decries what he terms the "return to nostalgia" thereafter. As such, he joins the ranks of the enemies of living traditions. Whatever their motivations, they are disempowering regular folk from doing important things more effectively by knocking them off the shoulders of those who came before, forcing them to learn everything for themselves without the benefit of the hard-won wisdom of their predecessors, resulting in the overall quality of work done being much less than what it could have been because there are far fewer geniuses than everyday folk. Nowhere is this decline in quality of everyday work more apparent than in architecture.

Culture-Wide

Living Traditions in architecture or urbanism begin as an insight conceived by a single person for how to build something better. If built, the second test is whether it resonates with a hive of like-minded individuals. If so, the pattern can become a cause for that hive, the members of whom recognize its value. If resonant, the third test is whether they build it repeatedly. If so, the pattern can launch a movement among the demographic group(s) in which the hive resides. If repeated widely, the fourth test is whether the pattern crosses the boundaries of its native demographic group(s) and is adopted by the culture at large into its family of regional Living Traditions.

Cross-Generational

There is a second route a pattern can take from initial conception by a single person to a Living Tradition. Demographic boundaries in a culture often have to do with cultural origins, economics, and several other factors. Sometimes, generational identification can be stronger than several other demographic features combined. Consider the generational identifications of the 1960s in the US when the "Generation Gap" moniker was coined. Because of the cultural upheavals of those times, generations banded together in conflict with other generations even though they shared other demographic factors across generations. So whether culture-wide transmission as described above is the final step to adpotion or whether it is cross-generational largely depends on societal conditions at the time, and the end result is the same: a pattern adopted into the family of regional Living Traditions.

Cautions

"Follow your heart" has permeated popular culture in art, song, film, and verse for my entire lifetime, dismissing in one generation what humanity has learned about the heart of our being over many of preceding generations. The warning to be careful of what we love has existed for millennia, and it holds every bit as true today. These are a few of the longstanding tests of things we love which I've found useful:

"Love your neighbor" is key to healthy community.

"Honor your father and mother" opens our minds to retaining long-proven things from those who came before us, completely counter to the Modernist attitude of "nothing that came before us is worthy of us."

The call echoing across the ages to respect nature in its processes and all it produces is a guide to not despoiling what feeds us in body, mind, and maybe even spirit if we're attentive enough to what we see and hear.

Original Green Ideals are my best attempt at adding to the list of useful tests. Do the things we love help us become more patient, or are we forever rushing headlong into the next expedient thing? Are we generous in all we do, seeking to help others with useful things we've experienced and learned ourselves? And do we love things that help us build connections between people, their places, and all that shelters them?

Living Tradition Tools

New Urbanists have developed several useful community-building tools over the past 45 years of the movement, and have adopted a number of other tools developed by place-makers who preceded them. These are arguably the most essential ones.

Town Founders

Prior to Seaside, developers across the US were more often than not considered greedy scoundrels intent on exploiting everything within and especially around their development sites. This attitude was not without merit, owing to the track record of the Industrial Development Complex after WWII. Robert and Daryl Davis, Town Founders of Seaside, Florida changed all that. Their many-faceted legacy begins with Generosity. Their early Seaside work began by setting up a seafood shack on County Road 30-A where they enticed travelers to stop awhile with free seafood. That might sound like just another marketing gimmick, but what came soon afterwards was more substantial. When TIME published Seaside as "The Little Town That Changed the World" developer interest in Seaside blew up. So Robert and Daryl invited them down to see what they were building, hosting them and feeding them, then doing the unthinkable (for developers) and opening up their books to their guests to show the financial side of how they were doing it.

When I asked Robert about that in recent years, he said "we were first known as 'the two crazy people on 30-A enticing people off the road with seafood'. And as long as we were the only ones building New Urbanism, it was likely to stay that way. But if we helped other developers learn how to do what we were doing, we would instead be known as pioneers in a new movement. So that's what we did because we'd much rather be considered pioneers than a crazy couple."

That ethic of generosity has continued within the New Urbanism until the present day, and not just among Town Founders, but also among planners beginning with Leon Krier before Seaside had even broken ground, then later with the Urban Guild and other entities within the movement to the point that it is now pervasive. Thanks in large part to the original Town Founders.

Town Architects

The modern-day Town Architect role began with Teofilo Victoria at Seaside in 1981 when members of the charrette team threw his backpack off the departing bus. When he got off to retrieve it, the bus pulled away as they shouted “you’re now the Town Architect!” To date, the Town Architect has largely worked for Town Founders at new developments.

I’ve been approached by existing towns, but they concluded it would be a legal nightmare, maybe even a “taking” for a town to regulate design anywhere except in a historic district. The difference between an existing town and a new one is that in the new one, the landowner and the town leadership are one and the same: the Town Founder. In an existing town, there are many landowners who could say “you’re damaging my right to sell by regulating design.” I’m trying to change that by changing the Town Architect role.

Almost everywhere reviews are taste-based, meaning that the premise is “thou shalt do this because I have better taste than you.” People might comply but nobody likes it. Often it devolves into a spitting contest. Instead of taste-based reviews, I’ve developed a principle-based review system based on “we do this because...”, which is the Kernel of the Living Traditions Operating System. This allows everyone to think again, which is the basis of a true living tradition.

It also creates far more variety than I’d think of on my own. I’ve done well over 10,000 reviews over the years, which is probably more than any other Town Architect alive today. My principle-based system evolved through trying pretty much every other system and seeing how they each fail. We plan to establish a community of Town Architects and other design reviewers soon where we can share best practices of design review, and I'm working on the Design Review Handbook as another route of spreading best practices we've all learned over the years.

Pattern Books

The first golden age of American architectural pattern books was 1829 to 1850, although they persisted through the end of the nineteenth century, with Minard Lafever, Orson Fowler, Alexander Jackson Davis, and Samuel Sloan being some of the more influential authors. Pattern books of that day were more akin to what we would call “plan books” today, laying out a collection of complete house plans and elevations which greatly influenced design and construction throughout the westward march of the United States to the Pacific. The rise of Modernism in the early twentieth century seemingly relegated pattern books to the dustbin of architectural history.

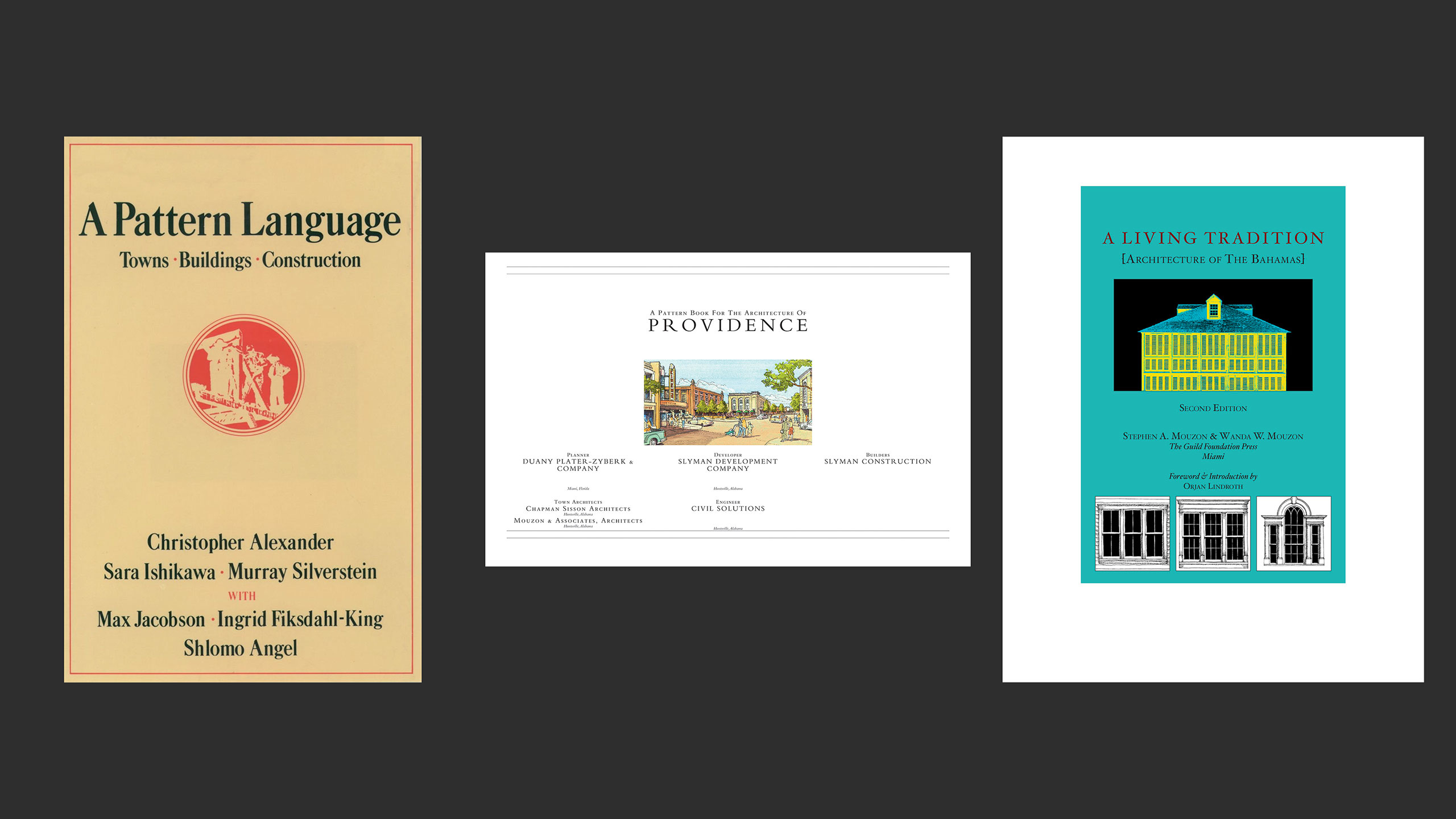

Christopher Alexander’s hugely influential A Pattern Language (1977) flipped the script, being a true book of patterns with no complete building designs. In doing so, it created the power to create countless buildings instead of containing only a couple hundred home designs.

For a more complete story on pattern books, see Pattern-Based Languages.

Guilds

Nathan Norris and I cofounded what is now known as the Urban Guild in 2001 with 13 original members. Today, it numbers dozens more professionals adept at working at the intersection of architecture and urbanism, designing places people love. The three core values of the Guild are humility, creativity, and generosity. The work of the Guild today focuses on collaboration, education, and awards.

Living Tradition Benefits

Why is a rainbow the iconic image of the benefits of living traditions? It is the combination of two things (sun and rain) that are usually mutually exclusive, just as a living tradition is the combination of both exploration and expertise. And while living traditions in architecture today are rarer than rainbows, when either one occurs, it produces great beauty naturally.

A living tradition is both expert and explorative. It doesn't care when good ideas came from; it uses them to build good places & buildings. The right question isn't "how old is it," but "how useful is it to us today?"

Economic Health

Lasting economic health is best measured by Main Street, not Wall Street. Global economies make turns far beyond the influence of any of us. Local economies, on the other hand, are the results of our work, and the work of our neighbors.

Environmental Health

This image illustrates pristine, undisturbed nature. And that is one measuring point of environmental health. But humans are part of nature as well, and so measures of environmental health must be taken all along the transect from undisturbed nature to the urban human environment.

Human Health

There are three realms of human health: physical health (illustrated here by the runner), mental health, and spiritual health, however you choose to define it.

Living Tradition Guides

The following are proverb-length ideas I've found useful in guiding work with living traditions:

Test tools & practices with this question: if we died tomorrow, how long would these things continue on their own? Movements begin on the backs of champions, but continue when they take on a life of their own and spread, even after the champions are gone.

It is far more effective to sow seeds and nourish them into something that can then spread on its own without you than to do something that dies with you. The ultimate goal of every specialist should be to make themselves unnecessary someday.

A tradition at its core is the assembled wisdom of a culture about things known to work well in a particular discipline such as urbanism or architecture. Those who oppose traditions oppose stuff that works.

A dead tradition is one where people simply follow rituals because it was handed down to them by their parents or other predecessors, and things no longer change. A Living Tradition is one where people are still figuring out new things within the core principles of the tradition.

Any idea, so long as its expression remains obscure, is unlikely to spread very far. A true Living Tradition is broadly understood by its participants.

“Innovation” is a two-faced word: innovation to achieve novel things is a destroyer of wisdom, discarding things long proven to work in favor of the new. Innovation to achieve better things builds on wisdom of things proven to work and is at the heart of a Living Tradition.

A living tradition sets itself apart from a dead tradition by humility: recognizing it can fail. And having the child-like wonder that there are things yet to be discovered which we may find, but don’t yet know. A dead tradition is “because I told you so.”

Let’s use the process of tradition to improve human endeavors like architecture (which it can do) but let’s not pretend it can elevate things to perfection (which it cannot do).

Styles are complex, with lots of rules, histories & somewhat different meanings in different regions. People’s attachment to or rejection of a style are complex as well, making style-based conversations likely fruitless. I have much better luck talking about individual patterns within Living Traditions.

Preservation began in the US because the buildings we gain for the buildings we lose are almost always a wretched downward trade in the past century. The only way to stop that is to help foster new Living Traditions that produces better buildings, not hideous ones. Preservation on its own is forever a losing battle because one by one old buildings will be lost to both economic and natural causes, leaving us someday with only the very best and most ferociously-preserved. But if we build lovable buildings anew, that is a sustaining process.

Search the Original Green Site

Buy the Original Green book on Amazon

Rather Buy Indie?

Contact Sundog Books at Seaside, which is our favorite bookstore ever!

Speaking

I speak on the Original Green across the US and abroad. Would you like for me to speak (via Zoom these days) at your next event?

Got an idea?

If you have an idea for a story, or know about work we need to feature...

Subscribe

... to receive periodic Original Green news releases. Here's our full Privacy Policy, where you'll see that we will not share your info with anyone else, nor will we sell it to anyone. All three fields required.

Home

Origins

Foundations

Nourishable Accessible Serviceable Securable Lovable Durable Adaptable Frugal Education Economy Culture Wellness

Resources

Original Green Scorecard Initiatives Presentations Reading List Quotes Links Tweetroll

Stories

OGTV

Media Room

Bios Press Speaking

© 2021 Mouzon Design, Inc.