Lovable Buildings

If a building cannot be loved, it will not last. It has long been known that unlovable buildings tend to be demolished and carted off to the landfill soon after they have paid back their initial investment. And once demolished, the carbon footprint of the building is meaningless.

Very few Americans make the connection between density, charm, and character when they travel to Europe. They complain fiercely about eight units per acre in the US, but love 100 units per acre in Europe. The difference, of course, is that so much of what was built in Europe in the 19th Century and earlier is deeply lovable while institutional multifamily projects slopped out in the US in recent decades are completely unlovable. The character makes all the difference.

I gave up on the term "beauty" years ago because the debates are endless, dating back to the philosophical proposition that "beauty is in the eye of the beholder." I now use the term "lovable" because while the architects will still debate if you give them a chance, the people are much clearer on what can be loved and what's unlovable.

Lovability Distinctions

The following are several distinctions of what is meant by the term "lovable," beginning with the distinction between the terms "beauty" and "love," then moving on to other distinctions such as between things that sound almost identical such as things built cheap versus things built of free materials, and why our budgets can't see much difference while to our hearts the difference can be enormous.

Beauty vs. Love

This young model was taking a quick break from a photoshoot in her island nation when she saw me photographing the plaza below her balcony. She struck this pose for me and I captured it; she gave me a thumbs-up, so I guess it's OK to use the photo, even though I spoke hardly a word of her language. Many have asked me over the years "why is Original Green architecture based on lovable things instead of beautiful things?" No single image captures the reason why better than this one. I admired her beauty that day, but I never loved her. I walked away to shoot the next plaza, and she turned back to her photoshoot. Wanda, on the other hand, changed my life in so many ways when I fell in love with her. So while beauty moves us to admiration, love moves us to action, and is therefore a stronger standard.

There's also the "beauty is in the eye of the beholder" thing that goes back in various forms all the way to antiquity. This has moved many (especially the architects) to discount beauty as a meaningful standard. But architects aside, there is strong agreement among people of many cultures what is lovable and what is unlovable where they live. The architects and design geeks may be confused on this, but the people generally are not.

Cheap vs. Free

The first scene was produced with some of the cheapest industrially-produced building materials available today; the second scene was created by hand, with materials picked up freely, probably within sight of where the building is built. Both scenes occurred within a short distance of each other, with the same regional conditions and climate, and built by people from the same culture. Viewed through the lens of economics, one would say that there's not much difference between cheap and free. But viewed through the lenses of human eyes, it's clear that there is a world of difference. But why?

The first scene was produced with some of the cheapest industrially-produced building materials available today; the second scene was created by hand, with materials picked up freely, probably within sight of where the building is built. Both scenes occurred within a short distance of each other, with the same regional conditions and climate, and built by people from the same culture. Viewed through the lens of economics, one would say that there's not much difference between cheap and free. But viewed through the lenses of human eyes, it's clear that there is a world of difference. But why?

To achieve industrial efficiency, mass-produced building products are manufactured to fairly precise standards so they roll off the assembly line just alike and pack tightly for shipping. But when they meet the real-world conditions of people building with the cheapest materials they can buy, they are often installed in imprecise ways, which looks sloppy at best, whereas construction of free materials, when built to even less precision, looks charming, as the second scene clearly shows.

So are there good uses for industrially-produced building materials? Yes, but it's important that the designers using precise materials be skillful enough to actually use them precisely. Alys Beach, for example, is built mostly of concrete blocks, just like the buildings in the first scene. But because the talents of most people designing there are world-class, they have built a stunningly beautiful place.

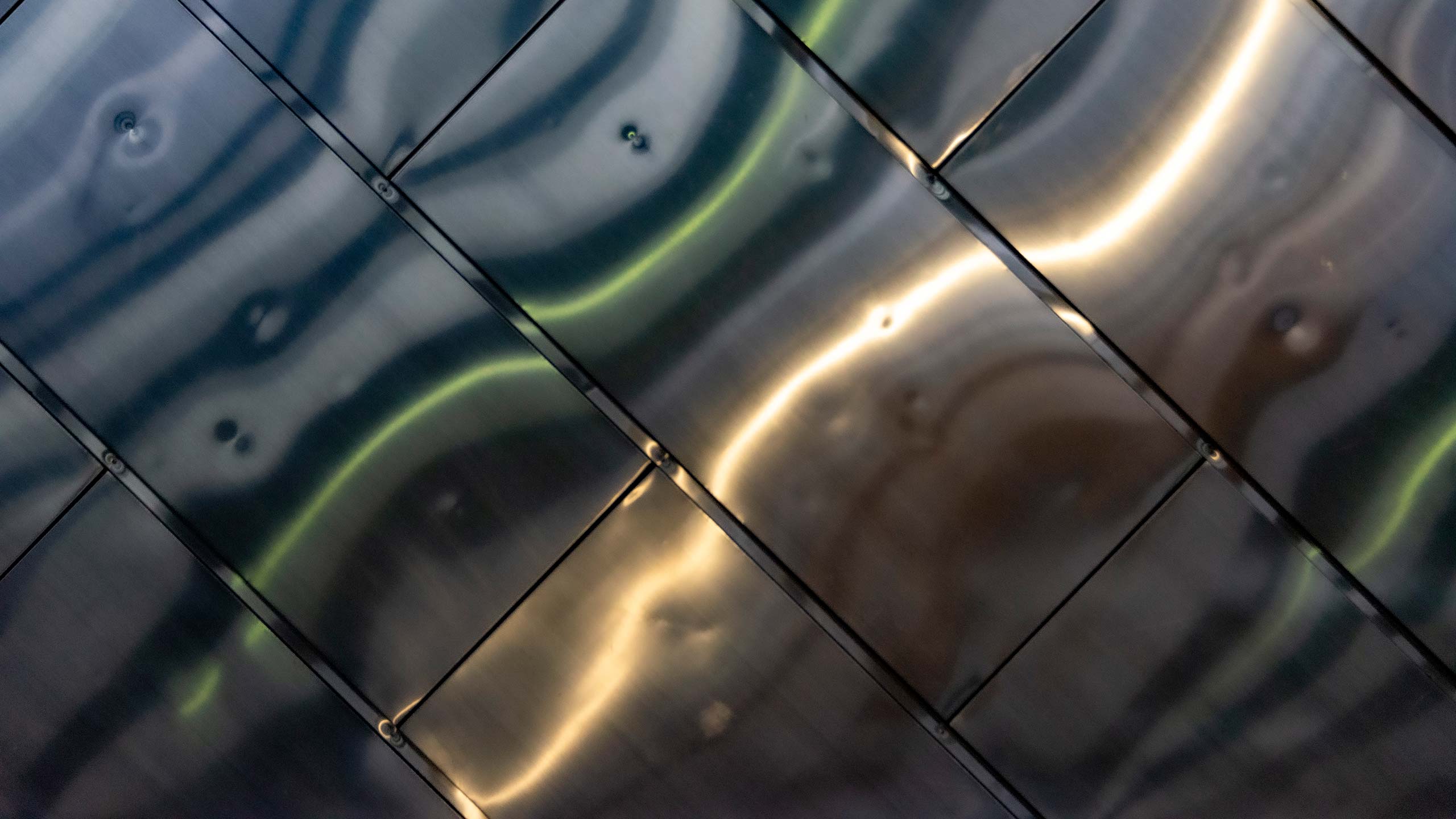

Perfection vs. Aging

How will your design look in its later years, after the age comes on? The surface in this first image was undoubtedly sleek and seductive in the beginning, but the dents with time are inevitable in a surface meant to be machine-perfect. The building just above has aged at least 100 times as long, but even in a state of lengthy disrepair, it is likely more endearing than in its original state, while the previous surface has begun to lose its luster. Design for perfection, and your work begins the long slide to demolition just after the ribbon-cutting. But if designed to age gracefully, it may be far more beloved long after you are gone.

Grain & Texture

Similar to the previous story on perfection vs. aging, both the ladder and the metal panels against which it is mounted have long since been retired from their original uses. But even though their first careers are receding in time, they are quite endearing in their second careers as story-tellers of the jobs they once did, including the wear and the scars of that earlier work. Aged humans can be endearing in similar ways.

The Carbon Stairsteps

This chart maps out the carbon impact trajectories of five building types. The green line noted Lovable Historic LEED is a historic building that has long proven its lovability by its long life, and has had all its equipment retrofitted to the highest standards. It has the shallowest rate of decline, due only to resource consumption to keep that highly-efficient equipment running. The yellow line for Lovable Historic Non-LEED has one distinction: its equipment has not been updated to today's highest performance standards. The bottom red line is the worst performance, and represents an unlovable building with ordinary equipment meeting no LEED standards. The downward steps represent the huge carbon impact when unlovable buildings are demolished and rebuilt because they cannot be loved; this shows a 40-year interval between rebuilds, although that's an average of several building types. Just above it is a similar line that represents an unlovable building, but with high-efficiency equipment. The highest stair-stepped line represents twice as good as LEED. The shocking thing is that over 200 years, a lovable historic building with no equipment upgrades tracks right along with an unlovable building twice as efficient as LEED buildings! For more information on the underlying assumptions and calculations, see the original post.

The Role of Living Things

Living things are essential to lovable places. Architects may focus on the beauty of the building to the left, but everyone else sees that the humble roof garden atop the parapet makes this a better place because while the building to the left shows signs of skill, the building with the roof garden shows signs of care.

Timelessness and Innovation

I've been struggling with a question that will likely get me in trouble across the board. I have for years said that it is my goal to build timeless places, where you can't know exactly when it was built, but can sense the it was built for humanity. But at what point does a new material or configuration earn the right to be part of a timeless thing? If nothing new were ever allowed, we'd all still be living in primitive huts. And should the canon of materials or configurations ever be closed? I'd make the case that living traditions have always incorporated new things and new ideas, otherwise they would never have evolved. But anyone with middling eyesight and a copy of Banister Fletcher can clearly see that living traditions evolve and mature. So what is the standard for admission of a new material or configuration into the canon of timeless place-making? I have no answers on this issue; only hunches.

Three Foundations of Lovable Things

For a couple millennia, we have been reminded that there is no greater love than this: that someone would sacrifice their own life for those they love. Not just put themselves in harm's way in hopes of coming out fine on the other side, as countless soldiers have done since antiquity, but knowing how it will end. This does not happen for things; just for deeply loved creatures. Love for things is a lower standard. Nonetheless, when a place, a building, or some other thing is loved enough, it can inspire enough toil and care that it is sustained well beyond the lifetimes of those who first loved it so. There are many reasons for such love, but most of them fall into three families of things loved: things that reflect us, things that delight us, and things that bring us into harmony with the world around us.

Things That Reflect Us

The most well-recognized form of things that reflect us are "face buildings" as seen on the gable end of this carriage house, with two eyes, a nose, and a mouth. There is an entire book's worth of other such reflections of us in all our proportions, arrangements, and other aspects.

Things That Delight Us

This frontage garden provides both visual delight and, depending on the plants chosen, delightful smells as well. A frontage garden this good qualifies as a Gift to the Street, which is an imporant component of Walk Appeal, highlighting the fact that things that delight us strengthen many other elements of the Original Green, and aid in building places people love.

Things That Bring Harmony

Yes, it's a stair. But it also bears strong resemblance to the Golden Mean spiral, which is iconic of proportional harmony. But it's not exactly the Golden Mean spiral, highlighting the fact that things which bring us into harmony with the world around us need not be mechanically precise in most cases (except for musical harmony), but instead serve as reminders of the highly interconnected ways the natural world is woven together, in contrast to the disparate silos of the abstracted and industrialized world.

Tools for Building Lovable Things

Similar to things that reflect us, there's a book's worth of tools for building lovable buildings and places; these are just a few of the most obvious ones.

The Luxury of Small

We built a house for ourselves soon after graduation; it was meant to be a superinsulated, passively-conditioned house surrounded by a self-sufficient homestead. The house was right at 3,000 square feet, right in line with market expectations of the day. But because the appraiser didn't have any idea how to evaluate all the passive features we were using, his appraisal came in at $27/square foot, a ridiculously low number having no basis in any discernible facts. We literally had to finish the house on credit card debt to cover costs over and above what the bank would loan based on his appraisal. I've joked in the years since that we had to finish the house with cardboard and duct tape; it wasn't quite that bad, but we really struggled to pay for plain old drywall on the walls.

A couple decades later we moved to South Beach to collaborate with the New Urbanists in the region, and bought a condo in the same building with some of them. Our unit was 747 square feet, almost exactly a quarter of the size of the post-graduation house. The image above is the kitchen of the condo, and it's clear that we were able to use far better materials than we ever dreamed of using in the big house, not because we hit the lottery, but because there was a lot less surface area to cover. I know no better way to illustrate the luxury of small versus the poverty of big. Bigger is not better. Bigger is worse. Or in our case, much worse. Smaller is better; luxuriously better, in fact.

Celebration of Meeting the Sky

There is no better place for a burst of exuberance in a building than in the place where it meets the sky. In cultures around the world and over the centuries, this is where those who love what they're building adorn them most often.

Surface Adornment

Utilitarian buildings accomplish their intended purposes with just their necessary elements, but people have from earliest times adorned buildings that were special to them in some way with ornamentation that most often reflected plant, animal, and human forms. Modernist buildings are today adorned with elements that appear to be be anything from broken glass to the hammered concrete of Brutalism. Most people who are not architects prefer the earlier reflections of natural things, so do not hesitate to adorn buildings you hope to be special with things that call attention to the building's role in its community.

Water's Edge

Water's edge, whether small waters or great waters, has always been a significant and sometimes profound place to humans. Cities on the water should work hard to bring the people back to the water's edge. In another time not long ago, this was likely a concrete-piped underground storm sewer, but today it has been daylighted and forms a park's downhill border. But it's important to note that it delivers delight because people can come right up to it. Water's edges where the people can't go, either because of piping or other inaccessibilities, brings no delight.

Utilitarian Thoughtfulness

The iconic rooftop lanterns of Antigua Guatemala can admit light or exhaust air, or both, and they are beautiful. More recent utilities like the wires strewn thoughtlessly across the roofs are indicative of the shoddy approach to building utilities in our times.

Visibly Shed Water

Buildings that visibly shed water tend to be more lovable than those that tell you "trust me; I got this." That's because we're hardwired to sense which buildings are more likely to shelter us, especially in a place we've never been before. I believe this is at least in part a survival instinct.

Regional Materials

Lovable buildings tend to use materials from the region. They not only look more appropriate than industrially-produced products from halfway around the world, but they cost less to ship and support regional economies. So be a good neighbor.

Celebrate Simple Things

There is nothing particularly unique about the flowerpots in this image. Some are natural terra cotta, some are glazed, they're all filled with colorful blooming plants and hung from the handrails with simple wire hangers. But they make people smile. Including me when I took this picture and Wanda, who was with me and pointed them out to me as we walked by. Because it's simplicity worth celebrating.

Civic Art

Civic art is an unmistakable sign of a place that is loved. But there's the thorny issue of statues. Someone a previous generation wanted to honor might not be so appreciated by those in the present day. It is every generation's right to choose who they will honor.

Color

If there is a local color tradition that has lasted at least 7 years, then honoring it makes what you're building or refreshing more tied to the place & therefore more lovable. Why 7 years? It's my arbitrary attempt to separate traditions likely to last from fads that may not.

Tales & Tools

These ideas support the Lovable Buildings foundation of the Original Green. The Tales are on Original Green Stories, while the Tools are in Original Green Resources. Several of these ideas support other ideals, foundations, and the Living Tradition Operating System because the Original Green is massively interlinked, so you'll see them listed wherever appropriate.

Search the Original Green Site

Buy the Original Green book on Amazon

Rather Buy Indie?

Contact Sundog Books at Seaside, which is our favorite bookstore ever!

Speaking

I speak on the Original Green across the US and abroad. Would you like for me to speak (via Zoom these days) at your next event?

Got an idea?

If you have an idea for a story, or know about work we need to feature...

Subscribe

... to receive periodic Original Green news releases. Here's our full Privacy Policy, where you'll see that we will not share your info with anyone else, nor will we sell it to anyone. All three fields required.

Home

Origins

Foundations

Nourishable Accessible Serviceable Securable Lovable Durable Adaptable Frugal Education Economy Culture Wellness

Resources

Original Green Scorecard Initiatives Presentations Reading List Quotes Links Tweetroll

Stories

OGTV

Media Room

Bios Press Speaking

© 2021 Mouzon Design, Inc.